The remains of a dead star harbors dust so cold, it is difficult to even see.

1E0102.2-7219

Dust is the ultimate underweight champion of the universe. Particles 1000 times smaller than the width of a single human hair influence every aspect of the Universe. If you want to study astronomy, dust is unavoidable. It likely accounts for less than a percent of the Universe and yet, you have to account for it. It reddens, scatters, and absorbs light from stars. It wingmans for hydrogen, allowing molecular hydrogen to form efficiently by shielding it from radiation and giving it a site to form. Dust is tiny, but it has got a huge heart. Despite its disproportional significance, it is not entirely understood where it all comes from.

Dust is mainly produced during supernovae events, in the circumstellar envelope of asymptotic giant branch stars, and grows in the insterstellar medium, but some submillimeter high redshift galaxies (who are too early for the lower mass star option) are observed to be extremely dusty. That leaves supernovae as the likely culprit for the vast majority of the dust in those galaxies. But when we look at supernovae close to us, it doesn't look like they produce much at all. This is known as the dust budget crisis. Where is all the dust, especially in the early Universe, coming from? To answer this question, we need to look much closer at these supernovae events.

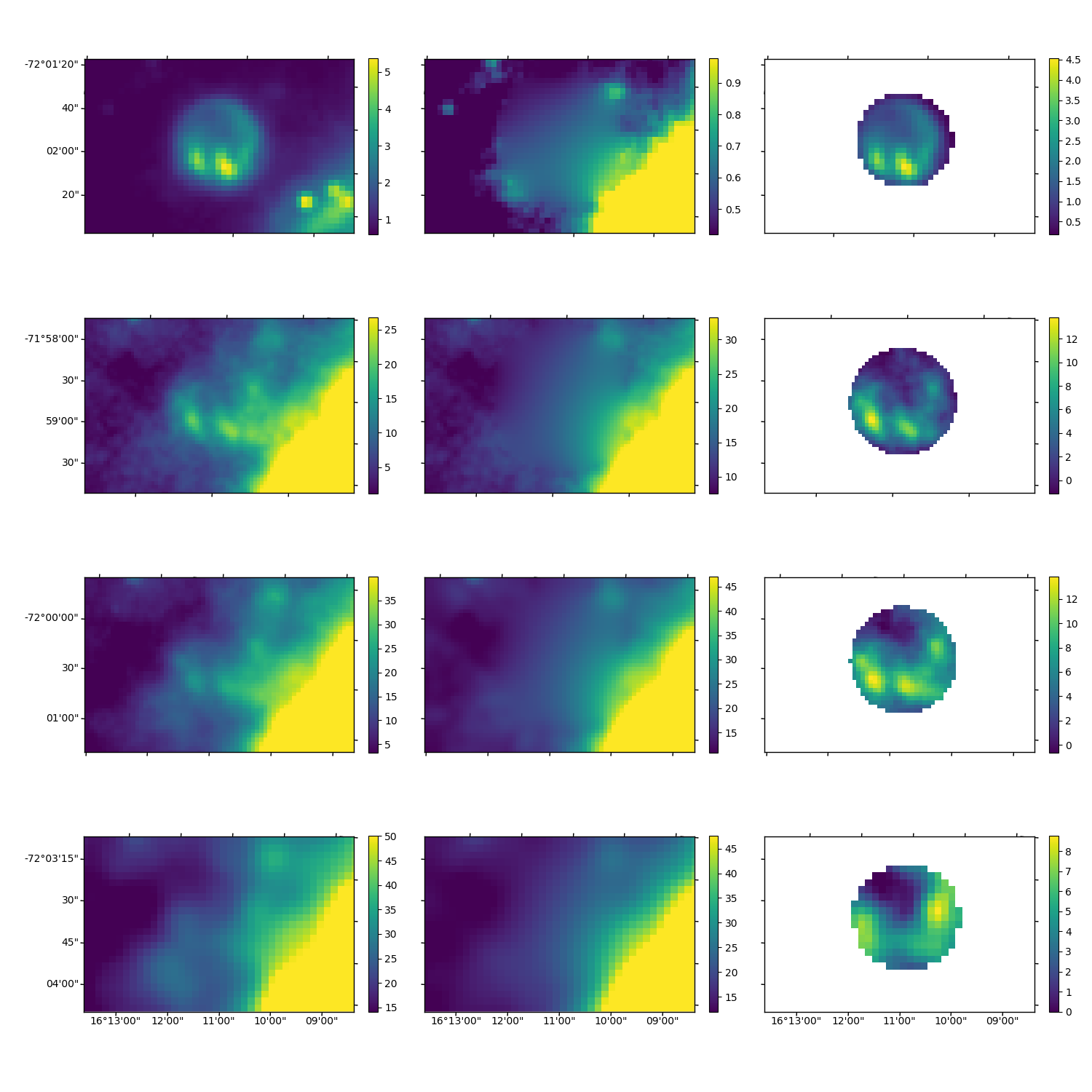

Figure 1: E0102 observations (from top to bottom) at 24, 70, 100, and 160 μms. The first column contains the original images. The second column is the modeled background. The third column is the subtracted remnant.

Figure 1: E0102 observations (from top to bottom) at 24, 70, 100, and 160 μms. The first column contains the original images. The second column is the modeled background. The third column is the subtracted remnant.

1E0102.2-7219, or for simplicity E0102, is a relatively young remnant on the order of about 1,000 years old. This youth is a good thing because it means the reverse shock from the initial explosion hasn't made its way into the ejecta to destroy the initial dust created by the remnant. Observations of young remnants such as 1987A, and Casseiopeia A, have actually shown a surprising amount of dust so we expect that E0102 would be no different. Yet previous measurements predicted that this would not be the case. For the first time, we present new Herschel observations of E0102 at 70, 100, and 160 μm wavelengths and with Spitzer 24 μm observations we detect a substantial body of cold dust previously undetected in the remnant!

The biggest challenge in measuring the amount of dust produced by a supernovae remnant is being able to adequately remove a spatially variable background. E0102 is in the Small Magellanic Cloud and the bright corner seen in Figure 1 is the N76 nebula. It's important that any foreground or background dust emission created by E0102's environment be carefully considered before measurements can be made. I developed and utilized a potentially new (to astronomy) strategy of removing the background. As it turns out, this strategy is already known in some engineering and image analyses fields as non linear diffusion-based inpainting. (For a review of image inpainting practices see: Image Inpainting: Overview and Recent Advances by Christine Guillemot and Olivier Le Meur.) This method is essentially an iterative solution to Laplace's equation by discretizing the heat equation using backward finite difference in time and second order central difference in space.

Look Ma, I made a Supernova Disappear:

def StepForward(data, timestep) :

xLim, yLim, junk = np.shape(data)

# Alpha should be small to slow convergence.

alpha = 0.1

for i in range(1, xLim-1) :

for j in range(1, yLim-1) :

# Discretizing heat equation

# Backward Finite Difference in Time

# Second Order Central Difference in Space

data[i,j,timestep] = data[i,j,timestep-1] + alpha * ((data[i+1,j,timestep-1] - 2*data[i,j,timestep-1] +

data[i-1,j,timestep-1]) + (data[i,j+1,timestep-1] - 2*data[i,j,timestep-1]

+ data[i,j-1,timestep-1]))

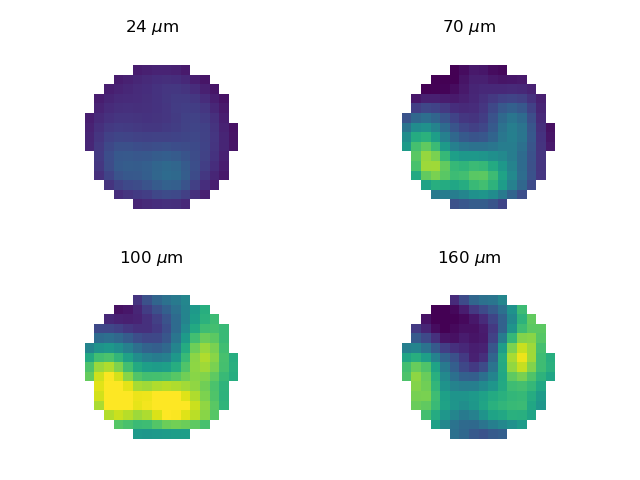

Figure 2: Supernovae remnants with background subtracted, convolved and regridded to the same lower resolution of the 160 μm image. The colorbar is the same for each of these four images with dark purple being the lowest and yellow being the highest intensity values in each infrared map.

Figure 2: Supernovae remnants with background subtracted, convolved and regridded to the same lower resolution of the 160 μm image. The colorbar is the same for each of these four images with dark purple being the lowest and yellow being the highest intensity values in each infrared map.

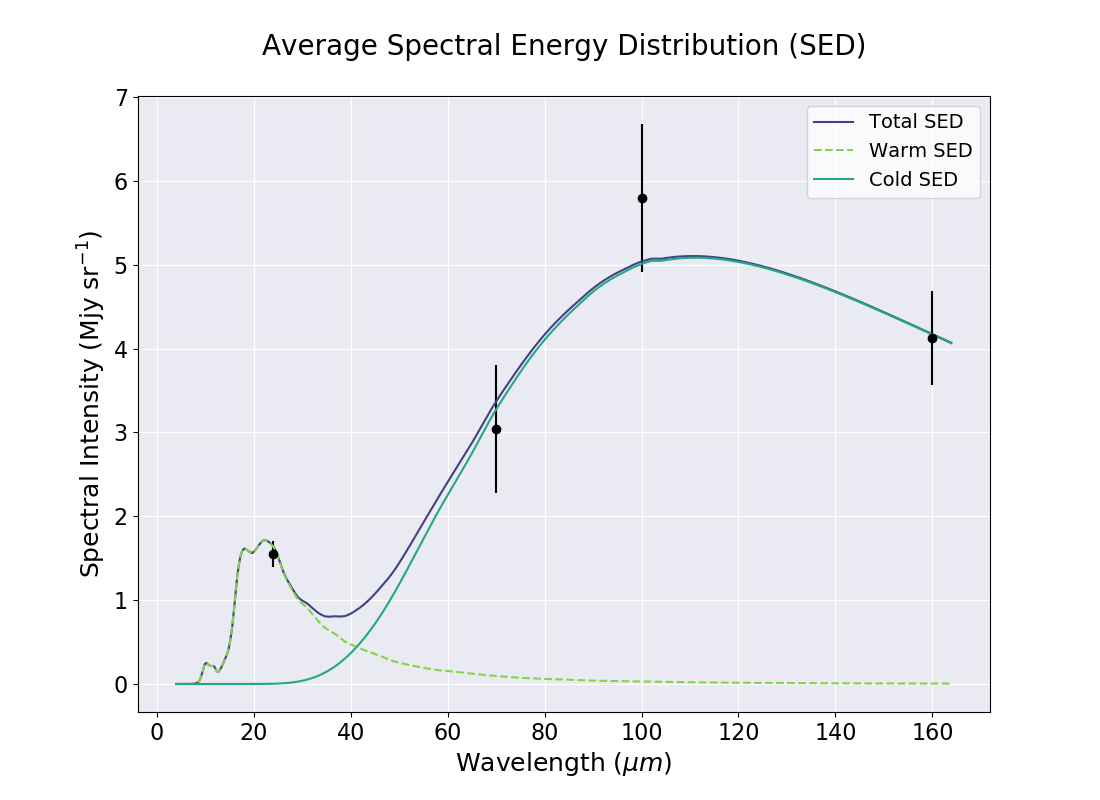

The final step is to take our measurements and model a modified black body equation to the spectral intensities in each image. The most straightforward way is to take an average of each image and fit them as seen in Figure 3. Depending on decisions we make about the error in our methodology, we arrive between 0.10 and 0.16 of a solar mass of dust in the remnant. Compared to the previous prediciton of ~0.003 solar masses, this is a substantial amount of dust! The second consideration is to fit each pixel in the remnant individually with constraints that we not include pixels that are below a detection limit of 2 sigma. This is the current last bit of the project that is being worked on. After evaluating the final measurements and our associated errors we will be free to submit!

Figure 3: Average intensity in Spitzer 24 μm image and in Herschel 70, 100, and 160 μm images fit by a modified black body spectrum. The error bars here are from the standard deviation in a blank sky region and a 10% calibration error. Using these errors we achieve at least a tenth of a solar mass of dust in the supernova remnant.

Figure 3: Average intensity in Spitzer 24 μm image and in Herschel 70, 100, and 160 μm images fit by a modified black body spectrum. The error bars here are from the standard deviation in a blank sky region and a 10% calibration error. Using these errors we achieve at least a tenth of a solar mass of dust in the supernova remnant.

The paper for this project is currently in prep.

This project is advised by Dr. Karin Sandstrom at the University of California in San Diego. I would like to thank her for years of astonishing amounts of patience, and for teaching me not to name my variable's "chai"or call comments "hashtags" as my trecherous millenial brain is wont to do.

I would also like to acknowledge Armando Armijo for his lessons in programming and for enabling me to prentiously call hashtags: "octothorpes."

Finally, I would like to acknowledge Clayton K. Anderson for his unwavering support and advice on writing algorithms, creating to do lists and for distracting me with quirky machine learning projects.